Bereavement behind bars: Grief support groups with and without therapy dogs for incarcerated females

Yvonne Eaton-Stull

Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania

yvonne.eaton-stull@sru.edu

Jessica Hotchkiss

Pennsylvania Department of Corrections

Janel Jones

Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania

Francine Lilien

Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania

Abstract

Grief is a universal experience;

however not everyone experiences grief and loss in the same way. People who are

incarcerated are often informed of losses via phone, are unable to attend

funeral services or participate in supportive rituals, and can have difficulty

expressing feelings in a place where showing emotion can be dangerous. Being

unable to obtain support and process grief and loss may contribute to impaired

functioning. In this study of bereavement support for women in prison,

incarcerated women with recent or unresolved losses (n=32) were randomly

assigned to grief support groups with therapy dogs (animal-assisted, AA) or

without therapy dogs (non-AA). Pre- and post-test measures of bereavement

symptoms and prolonged grief disorder (PGD) were obtained. This study shows

that AA groups had more significant decreases in symptoms, lower rates of

post-group diagnostic criteria for PGD and higher rates of perceived

support/benefit from the groups.

Practice points

1. Animal-assisted support groups show promise as a therapeutic bereavement modality.

2. Practitioners can utilise therapy dogs to assist in decreasing bereavement symptoms.

3. Animal-assisted therapy can be beneficial in reducing prolonged grief disorder.

4. Therapy dogs can assist in facilitating the tasks of grieving.

5. Support groups for grieving, incarcerated women are essential in facilitating coping with loss.

Key words

animal-assisted therapy, therapy dogs, grief, group therapy, loss, prison, women

Introduction

The death of a loved one can be one of the most difficult experiences in life. Imagine how this could be compounded if one was isolated and separated from supports or unable to participate in funerals or other healing rituals. For those who are incarcerated, this is exactly the case. Moreover, those who are incarcerated typically experience the loss of loved ones at high rates with 91% of institutionalised youth experiencing high rates of multiple and traumatic losses (Vaswani, 2014) and nearly 50% of women in prison experiencing the death of a close family member (Harner et al, 2011). Elsewhere, in a larger study of 667 incarcerated older adults, 60% experienced an unexpected death while in prison and 70% experienced an anticipated death (Maschi et al, 2015).

The experience of grief resulting from these deaths while incarcerated is compounded by separation from support networks (Taylor, 2012). For those experiencing a death of a loved one while incarcerated, they do not have family support, are often unable to attend funerals or other rituals, fear expressing their emotions, and lack the comfort of touch (Harner et al, 2011). Aday and Wahidin (2016) describe the grieving process as being suspended while a person is in prison. Those who are imprisoned experience disenfranchised grief due to being unable to effectively acknowledge, express and mourn their loss (Masterton, 2014).

In fact, Wilson (2013) indicates that incarcerated women are one of the most disenfranchised members of our society. This high rate of disenfranchised grief within the prison population has been linked with prolonged grief disorder (PGD), the psychiatric diagnosis that stemmed from complicated or traumatic grief (Leach et al, 2008). Boelen and Prigerson (2007) define PGD as persistently elevated symptoms of grief with problems adjusting to the loss and suggest that this disorder is often related to decreased quality of life and other mental health issues. In a study with 33 young offenders, Vaswani (2014) found that mental health difficulties increased when coupled with bereavement and indicated that opportunities to talk in prison environments can be beneficial in facilitating the grieving process. Assisting individuals in emotionally processing their loss is critical in decreasing PGD severity as well (Bryant et al, 2014). This is particularly important for those who are in prison and detached from support networks and rituals. For those who are incarcerated, treatment staff, including social workers and psychology staff, often fulfill this role.

Grief support in prison includes providing a safe place for one to express feelings and receive validation from others (Taylor, 2012). Group intervention can also assist during the grieving process. Stevenson and McCutchen (2006) show that groups help to increase feelings of self-worth, sense of control, and hope for the future while decreasing anger, guilt and violence. In a grief intervention for incarcerated youth, trauma-focused groups resulted in a significant decrease in depression and anger (Olafson et al, 2018). In a recent randomised trial with prisoners that utilised interpersonal psychotherapy groups (IPT) participants, provided with an opportunity to express their feelings and address their needs, experienced decreased symptoms of depression, PTSD and hopelessness (Johnson et al, 2019). Bove and Tryon (2019) studied experiences of incarcerated women sharing their stories, including those of grief and loss, to others. This process of sharing identified relevant themes of making a contribution, connecting with others, identifying and expressing emotions, identifying growth and moving on (Bove & Tryon, 2019).

The use of therapy dogs by practitioners is gaining popularity and an evidence base. In fact, two recent systematic reviews of animal-assisted therapy found beneficial effects for mental health (Borgi et al, 2020; Jones et al, 2019). However, there are few studies investigating the use of animal-assisted therapy within the prisons and even fewer for incarcerated females experiencing loss. In a male prison, Fournier et al (2007) found interventions with therapy dogs had significant reductions in the amount of infractions and improvement in social skills. In 2013, Jasperson provided an animal-assisted psycho-educational group to female offenders which led to decreased anxiety and depression and increased self-awareness and optimism. Jasperson's (2010) earlier animal-assisted intervention with incarcerated women also observed increased motivation to attend programming. Another study with incarcerated males found animal-assisted intervention (AAI) decreased stress and improved mood (Koda et al, 2015). Furst's (2006) national survey of prison animal programmes found that most programmes were geared toward community service (such as training shelter dogs to make them more adoptable) and were implemented in male facilities. Wood (2015) evaluated perceptions of non-incarcerated grieving men and women (N=10) who utilised therapy dogs in their treatment for bereavement. Wood's entire sample identified the importance of animal for bereavement counseling, comfort the animal brought to them in their grief, and the importance of touch (Wood, 2015).

In summary, the literature demonstrates that those who are incarcerated experience high rates of death and bereavement and lack the supports, rituals and comfort to process their grief which may exacerbate mental health issues. The importance of grief support, via groups, creates a supportive, validating environment with demonstrated benefits. The addition of therapy dogs into these groups has been shown to enhance motivation for treatment, offer mental health treatment benefits, and specifically provide physical comfort and touch not typically permitted in a prison environment.

Materials and methods

Building on this body of work, this research study sought to expand the research base of the benefits of therapy dogs in assisting bereaved individuals who are incarcerated. This study (within the US) was a collaboration between a Pennsylvania state university and a Pennsylvania state prison to provide grief support groups with and without AA to incarcerated adult females who experienced a recent or unresolved loss. The purpose of this intervention was to assist participants in decreasing distress from loss.

This research intended to answer the following questions:

1. Do female offenders who attend the support group experience a decrease in their bereavement symptoms?

2. Do female offenders who attend the support groups experience a decrease in diagnostic symptoms of PGD?

3. Will participants who attend the groups with therapy dogs (AA) have better results than the non-AA group?

Hypotheses

1. H1: Female offenders who attend the support group will experience a decrease in their bereavement symptoms.

2. H2: Female offenders who attend the support group will experience a decrease in their symptoms of PGD.

3. H3: Female offenders who attended the AA groups will experience better results than the non-AA groups.

Participants

Following the State Department of Corrections and university institutional review board approved research protocols, participants were recruited by the state prison psychological services staff. Flyers were hung within the institution and also advertised on the institution television channel. Participation was entirely voluntary, and interested individuals simply contacted the prison's psychology department to be considered for the study. Flyers did reference the possibility of dogs within some groups. Exclusionary criteria included any offender with an incident of violence within the past six months, history of cruelty to animals, and fear of, or severe allergies to, dogs. Willing participants were screened by the prison psychological services specialist for eligibility. Allocation into the control and AA treatment group was randomly generated by computer programme.

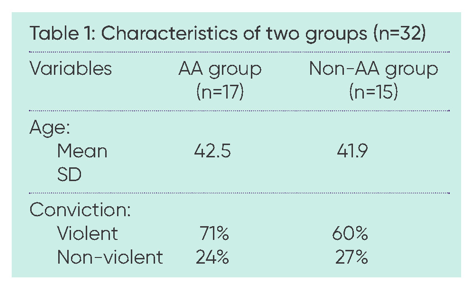

A total of 48 women enrolled in the research intervention, but only 43 showed up to the first sessions to sign consent forms and begin the programme; ultimately, a total of 32 participants completed the group interventions. Drop-outs occurred for a variety of reasons, including work conflicts, inability to attend programming due to being on restricted housing or in the therapeutic community, parole, or feeling unready to address their loss. Eligible women were randomly assigned to the group interventions. The first two non-AA groups (control) did not include any therapy dogs. The last two AA groups (experimental) integrated therapy dogs into each session for comfort and support. AA groups were able to hold and pet the therapy dogs as they wished. A comparison of group composition is provided in Table 1.

Research design

The structure for each group was based on Worden's (2008) tasks of grief: accepting the reality of the loss, processing the pain, adjusting without their loved one, and finding a connection while moving forward. All groups followed the same protocol and were conducted in the same manner:

1. Session 1: Introduction, consents, pre-test measures

2. Session 2: Accepting the reality of loss (sharing facts)

3. Session 3: Working through pain (sharing emotions experienced)

4. Session 4: Adjusing (coping strategies)

5. Session 5: Moving forward (memorialising)

6. Session 6: Conclusion, post-test measures.

Every group session lasted for one hour and occurred on the same day and time for a total of six sessions. Sessions one and six involved obtaining assessment measures. During sessions 2–5, worksheets from Zamore and Leutenberg's (2008) Grief Work: Healing from Loss, were selected to assist in the session task and provided to help participants express themselves. Two therapy dogs were included and available in every session of the AA groups. Participants could hold the smaller therapy dogs or position themselves on the floor to interact with them. Petting, hugging and receiving 'kisses' from the therapy dogs could be initiated by participants throughout each group. The therapy dogs were certified through the Alliance of Therapy Dogs (www.therapydogs.com), and included a Cavalier King Charles spaniel, a labrador retriever/beagle mix and a shih tzu. These dogs were specifically selected as they all had prior experience working in prisons; additionally, two were certified crisis response dogs and very comfortable (not stressed) and adaptable to different environments.

Measurements

An informational survey was gathered during the first session to obtain participant's history of incarceration, information on loss(es), and level of support they received from others to acknowledge and process their loss. Two formal assessment measures were also obtained, administered on the first and last sessions of the group. The first assessment, the core bereavement items (CORE) was used to evaluate symptoms of bereavement experienced (Burnett, 1997; Burnett et al, 1997). This 17-item questionnaire has questions to identify images and thoughts of their lost loved one, acute separation, and feelings of grief; participants identify the degree to which they have certain experiences, from never to a lot of the time. The second assessment used for pre-and post-test measures, the prolonged grief disorder (PGD) tool was a 13-item measure obtaining details about the diagnostic criteria for PGD including separation distress, duration of distress, symptoms (cognitive, emotional and behavioral), and functional impairment (Prigerson & Maciejewski, n.d.). In addition to these two assessment measures, a 3-item reflective questionnaire was obtained during the final session to gather information about the level of comfort and support they felt from group (on a scale from extremely supportive, very supportive, somewhat supportive or not at all supportive) as well as what aspects of the group participants found most helpful. Data was analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were obtained.

Results

Losses and support

The relational losses experienced by the AA group participants were most frequently parent (29.4%), child (29.4%), partner (23.5%), or grandparent (23.5%). The largest relational losses in the non-AA group included ex-partners (33%), aunt/uncle (33%), partner (26.6%), parent (20%) and child (20%).

Across both groups, more than one-third of participants reported a lack of support following their loss (35% of the participants in the AA groups and 33% of the participants in the non-AA group). For those that did receive support, family were the largest source (44.4% in the AA groups and 46.6% in the non-AA groups) followed by professionals (41.1% in the AA groups and 33.3% in the non-AA groups).

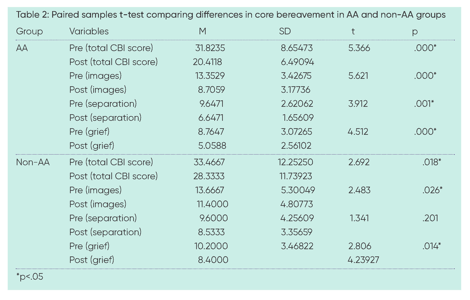

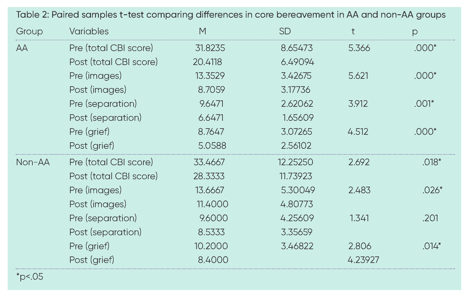

Core bereavement items

The core bereavement items questionnaire was administered on the first group session and again on the last. The paired-samples t-test is used to compare means of two scores from related samples (Cronk, 2017). Paired-samples t-tests were calculated to compare the mean pre-test scores to the mean post-test scores (Table 2). For the AA groups, the mean core bereavement score at pre-test was 31.8 (sd=8.65), and the mean core bereavement score at post-test was 20.4 (sd=6.5). For the non-AA groups, the mean core bereavement score at pre-test was 33.5 (sd=12.25), and the mean core bereavement score at post-test was 28.3 (sd=11.7). Significant decreases (p<.05) in core bereavement was found in both the AA and non-AA groups. The AA groups also had significant (p<.05) decreases in the other three measures: images and thoughts of their lost loved one, acute separation, and feelings of grief; whereas the non-AA groups only had significant (p<.05) decreases in two of these measures: images and thoughts of their lost loved one, and feelings of grief.

Prolonged grief disorder

Prolonged grief disorder (PGD) measures were also administered on the first group session as well as the last. 23.5% of participants in the AA group met the diagnostic criteria for PGD at pre-test, but none met the criteria at post-test. 33.3% of participants in the non-AA group met the diagnostic criteria for PGD at pre-test, and 13.3% at post-test. Chart 1 demonstrates the differences in pre- and post-test measures between the treatment conditions.

Reflection

A three-item reflective questionnaire was given to participants to share feedback about the groups. The first question asked participants to indicate how helpful the group was in terms of providing comfort and support to them; choices were extremely beneficial, very beneficial, somewhat beneficial, and not at all beneficial. Question two was an open-ended question for them to describe the most beneficial part of the group, and question three was for additional comments.

The two AA groups viewed the groups as more beneficial overall, with 71% indicating the groups were extremely beneficial and 29% indicating very beneficial. The non-AA groups viewed the groups as less beneficial: 40% extremely, 47% very beneficial, and 13% somewhat beneficial. No participants in either the AA or the non-AA interventions viewed the groups as not at all beneficial.

Qualitative comments were categorised and coded to identify common themes as to what the participants found most beneficial in the groups. Four themes were present in the AA groups: the degree of social support and understanding from others who are also grieving (65%), comfort and support received from the therapy dogs (59%), ability to express and share their feelings/loss (47%), and the skills/knowledge gained from treatment itself (18%).

Three of the same themes of benefits emerged in the non-AA group: 67% commented on the ability to express and share their feelings/loss, 60% commented on the social support and understanding received from others who are also grieving, and 40% felt the skills/knowledge gained from the treatment itself were beneficial.

Discussion

Results from this study provide support for AA-bereavement care for incarcerated women. All three research hypotheses were supported:

1. H1: Female offenders who attended the support group reported decreased bereavement symptoms.

2. H2: Female offenders who attended the support group reported decreased symptoms of PGD.

3. H3: Female offenders who attended the AA groups experienced better results than the non-AA groups in terms of core bereavement symptoms, PGD, and subjective view of the group's effectiveness. Qualitative data supported that of the quantitative data; that the AA group members responded more positively to the benefits of the group and its effectiveness.

The data showed that the integration of therapy dogs into this support group created a safe and comforting space for participants to share difficult emotions and stories. It is believed this innovative addition to group created a sense of caring that fostered expression of bereavement. Narrative comments talked extensively about the responsiveness of the therapy dogs; 'when I opened up and was in tears, Chevy came right over to me and comforted me in my grief', 'it's like they knew something was bothering us and came to comfort us', and 'I am going to miss the love of the dogs'. These qualitative comments demonstrate the support participants felt they received from the therapy dogs.

According to the relational theory, making connections with others is a primary motivator for women (Bove & Tryon, 2019). The qualitative results support the benefits of this group to make these connections with others who understand their grief. Group participants supported each other, often passing the smaller dogs to one another during difficult disclosures and emotions. Helping incarcerated women lessen their feelings of isolation by sharing their profound losses is essential to healthy processing of their experiences. Many participants in this study reported unresolved grief as a contributing factor to things such as drug use which may lead to further criminal behavior. Continuing, impaired functioning can also lead to challenges upon re-integration into society (Johnson et al, 2019). Further long-term measures, such as recidivism or post-parole follow up and assessment, would add valuable information to the long-term benefits of these interventions.

Challenges

Conducting research in prisons requires a little more planning, paperwork, and approvals to address concerns around vulnerable populations. Safety issues were also a concern addressed by the university institutional review board. Steps taken to limit safety issues included the use of well-trained, experienced therapy dogs and handlers. Additionally, exclusionary criteria (no history of animal cruelty, fear of or severe allergies to dogs or violent acts within the past 6 months) were applied to lessen concerns of safety.

The Department of Corrections appears very committed to permitting these research partnerships and collaborations to enhance services for those in their custody. There were some additional requirements imposed by the state prison, including their internal research review, security clearances, and security orientation. The weekly scans through the metal detectors and following prison protocol (such as sign-in process, ion scanning, and so on) required additional time. However, in the end, it was well worth it when you see the benefits of those from start to finish and hear the gratitude from participants for their ability to receive such an intervention.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

Animal-assisted treatment offers great value to those who are incarcerated, so it is sad there is not more treatment of this kind available in correctional settings. Due to the lack of animal assisted therapy research in prisons, reasons for lack of implementation are unclear. Limited availability could be because of a lack of awareness by prisons on how to access therapy dog teams to assist, or a lack of support from prison officials or a misunderstanding/misinformation of what constitutes animal assisted therapy. Another limitation may be the difficulty obtaining willing volunteers to bring their dogs inside a place they are unfamiliar with. As always, resource limitations are often barriers in delivering services as is shortages of qualified professionals willing to work in a prison (Johnson et al, 2019), and this may be the case for therapy dog handlers. Developing strong partnerships with universities and/or therapy dog organisations could therefore potentially help to bridge the gap and overcome some of these challenges so that individuals can continue to benefit from AAI while also expanding the evidence-base.

Prison dog programmes (Furst, 2006) are increasing in the nation, so perhaps using dogs already inside the prisons could offer additional opportunities to bereaved individuals in prison. Alternatively, a peer support specialist with a dog could be made available on request to bring the dog to a fellow inmate for support when they get the news of a loss or to participate in a grief and loss group.

Conclusion

Dealing with grief and loss is a reality we must all face in life, and regardless of one's criminal history, everyone, we argue, should have bereavement care to assist with coping. As indicated in this research, just offering a support group to share with others who have experienced similar loss is valuable. Evidence that this intervention decreases symptoms of bereavement, decreases the diagnosis of PGD, as well as promotes positive, subjective feelings of the benefits warrant further research and treatment of this kind. Including a therapy dog that can provide the physical comfort and support not typically permitted in a prison setting adds additional benefits for bereaved individuals. To conclude, from the insightful words of a participant, 'everything is better with dogs'.

References

Aday R & Wahidin A (2016) Older prisoners' experiences of death, dying and grief behind bars. The Howard Journal, 55(3) 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12172.

Boelen PA & Prigerson HG (2007) The influence of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety on quality of life among bereaved adults: A prospective study. European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience, 257, 444–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-007-0744-0.

Borgi, M, Collacchi B, Giuliani A & Cirulli F (2020) Dog visiting programs for managing depressive symptoms in older adults: A meta-analysis. Gerontologist, 60(1) e66–e75. https://doi-org.proxy-sru.klnpa.org/10.1093.geront/gny149

Bove A & Tryon R (2019) The power of storytelling: The experiences of incarcerated women sharing their stories. International Journal of Offender Treatment and Comparative Criminology, 62(15) 4814–4833. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x18785100

Bryant RA, Kenny L, Joscelyn A, Rawson N, Maccallum F, Cahill C, Hopwood S, Aderka I & Nickerson A (2014) Treating PGD: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(12) 1332–1339. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1600

Burnett PC (1997) Core bereavement items. Available at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/26824/1/c26824.pdf (accessed 12 November 2021).

Burnett PC, Middleton W, Raphael B & Marinek N (1997) Measuring core bereavement phenomena. Psychological Medicine, 27, 49–57.

Cronk B (2017) How to use SPSS: A step-by-step guide to analysis and interpretation. Routledge.

Fournier AK, Geller ES & Fortney EV (2007) Human-animal interaction in a prison setting: Impact on criminal behavior, treatment progress, and social skills. Behavior and Social Issues, 16(1) 89–105.

Furst G (2006) Prison-based animal programs: A national survey. The Prison Journal, 86(4) 407–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885506293242.

Harner HM, Hentz PM & Evangelista MC (2011) Grief interrupted: The experience of lost among incarcerated women. Qualitative Health Research, 21(4) 454–464. https://doi.org/10/1177/1049732310373257.

Jasperson RA (2013) An animal-assisted therapy intervention with female offenders. Anthrozoos, 26(1) 135–145. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303713X13534238631678.

Jasperson RA (2010) Animal-assisted therapy with female inmates with mental illness: A case example from a pilot program. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 49, 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2010.499056.

Johnson JE, Miller TR, Cerbo LA, Nagiso J, Stout RL, Zlotnick C, Andrade JT, Bonner J & Wiltsey-Stirman S (2019) Randomized cost-effective trials of group interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for prisoners with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychiatry, 87(4) 392–409. https://doi.org/10.1047/ccp0000379.

Jones MG, Rice SM & Cotton SM (2019) Incorporating animal-assisted therapy in mental health treatments for adolescents: A systematic review of canine assisted psychotherapy. PLoS ONE, 14(1).

Koda N, Miyaji Y, Kuniyoshi M, Adachi Y, Watababe G, Miyaji C & Yamada K (2015) Effects of a dog-assisted program in a Japanese prison. Asian Criminology, 10, 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-015-9204-3.

Leach R, Burgess T & Holmwood C (2008) Could recidivism in prisoners be linked to traumatic grief? A review of the evidence. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 4(2) 104–119.

Maschi T, Viola D, Morgen K & Koskinen L (2015) Trauma, stress, grief, loss, and separation among older adults in prison: The protective role of coping resources on physical and mental well-being. Journal of Crime and Justice, 38(1) 113–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2013.808853.

Masterton J (2014) A confined encounter: The lived experience of bereavement in prison. Bereavement Care, 33(2) 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682621.2014.933572.

Olafson E, Boat BW, Putnam KT, Thieken L, Marrow MT & Putnam FW (2018) Implementing trauma and grief component therapy for adolescents and think trauma for traumatized youth in secure juvenile settings. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(16) 2537–2557. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516628287.

Prigerson HG & Maciejewski PK (nd) Prolonged grief disorder (PG-13). Available at: https://endoflife.weill.cornell.edu/sites/default/files/pg-13.pdf [accessesd 12 November 2021].

Stevenson RG & McCutchen R (2006) When meaning has lost its way: Life and loss 'behind bars'. Illness, Crisis and Loss, 14(2) 103–119.

Taylor PB (2012) Grief counseling in the jail setting. American Jails, July/Aug, 39–42.

Vaswani N (2014) The ripples of death: Exploring the bereavement experiences and mental health of young men in custody. The Howard Journal, 53(4) 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/hojo.12064.

Wilson JM (2013) Agency through collective creation and performance: Empowering incarcerated women on and off stage. Making Connections: Interdisciplinary approaches to cultural diversity, 14, 1–15.

Wood EA (2015) An exploration of pet therapy for bereavement. (UMI Number 3708069) [Doctoral Dissertation, Capella University]. UMI Dissertation Publishing & ProQuest LLC.

Worden JW (2008) Grief counseling and grief therapy: a handbook for the mental health practitioner, 4th edition. Springer Publishing Company.

Zamore F & Leutenberg ERA (2008) GriefWork: Healing from loss. Whole Person.