Bereavement during the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK: What do we know so far?

Emily Harrop

Cardiff University, Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Centre, Division of Population Medicine

Lucy E Selman

University of Bristol, Palliative and End of Life Care Research Group, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School

Abstract

The

Covid-19 pandemic has been a devastating mass bereavement event, with measures

to control the virus leading to unprecedented changes to end-of-life and

mourning practices. In this review we consider the research evidence on the

experiences of people bereaved during the pandemic. We summarise

key findings reported in the first five publications from our UK-based Bereavement during COVID-19 study,

drawing comparisons with available evidence from other studies of bereavement

during the pandemic. We summarise these findings

across three main topics: experiences at the end of life and in early

bereavement; coping and informal support during the pandemic; and access to

bereavement and mental health services. The synthesis demonstrates the

exceptional challenges of pandemic bereavement, including high levels of

disruption to end-of-life care, dying and mourning practices as well as to

people's social networks and usual coping mechanisms. We identified

considerable needs for emotional, therapeutic and informal support among

bereaved people, compounded by significant difficulties in receiving and

accessing such support. We provide evidence-based recommendations for improving

people's experiences of bereavement and access to support at all levels.

Practice points

1. Improve communication with families at the end of life, enabling visiting and contact with patients as far as possible and providing better support immediately after a death. This post-death contact should include information-giving on bereavement services and opportunities to discuss the death/patient-care.

2. Greater resourcing and expansion of national and regional adult and child bereavement services, with strategies to improve awareness of bereavement support options for adults and children and young people. Information on services and self-help resources should be widely available in online and community settings.

3. Community, school and work-based based interventions/guidance should strengthen supportive networks and improve grief literacy, compassion and communication skills across society. When lockdown restrictions are in place, more flexible support bubbles should be permitted for the recently bereaved.

4.

Provide opportunities for remembrance,

greater respect and listening to those bereaved, including national and local

initiatives which support private and public remembrance; and inclusive

consultation with those recently bereaved (eg via the

UK Commission on Bereavement: bereavementcommission.org.uk)

Keywords

bereavement, grief, pandemics, coronavirus infections, bereavement services

As we

approach the second anniversary of the first Covid-19 reported deaths in the

UK, we consider the growing body of research evidence on the experiences of

people bereaved during this most devastating and disruptive of global

pandemics. We summarise key findings reported in the

first five publications from our UK-based Bereavement

during Covid-19 study, drawing comparisons with available evidence from

other studies investigating the experiences of bereaved people during Covid-19.

The Bereavement during COVID-19 study

includes a mixed-methods longitudinal survey investigating end-of-life

experiences (including experiences of care before and immediately after the

death), bereavement support needs and experiences in the UK during Covid-19.

Baseline data was collected from people bereaved in the UK from 16 March 2020

(of any cause of death), when the first infection control restrictions were

implemented, until 2 January 2021. The survey was open from 28 August 2020 to 5

January 2021 and was completed by 711 adults who had been bereaved between 1

and 279 days ago (median 152 days (5 months)).

The study

publications summarised here report on interim (Harrop et al, 2020) and full results from the baseline

survey (Harrop et al, 2021a; 2021b; Selman et al,

2021a; Torrens-Burton et al, 2021). We also include in the summary a

publication reporting results from the second round survey responses of 104

parent/guardian participants, who answered a question on the support

experiences and needs of their children, aged 25 or under (Harrop

et al, 2021b).

Here we summarise study findings to date in three main topics:

experiences at the end of life and in early bereavement; coping and informal

support during the pandemic; and access to bereavement and mental health

services.

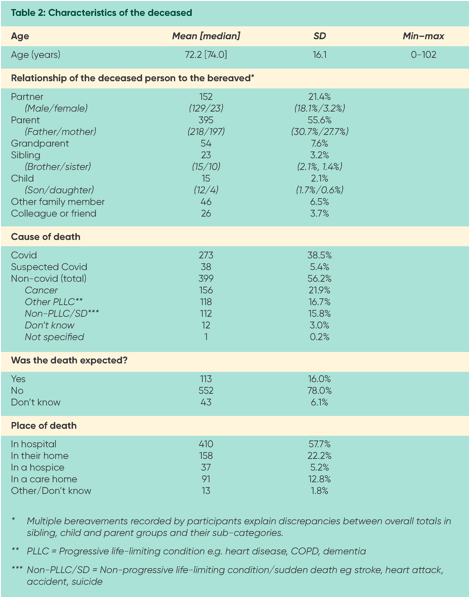

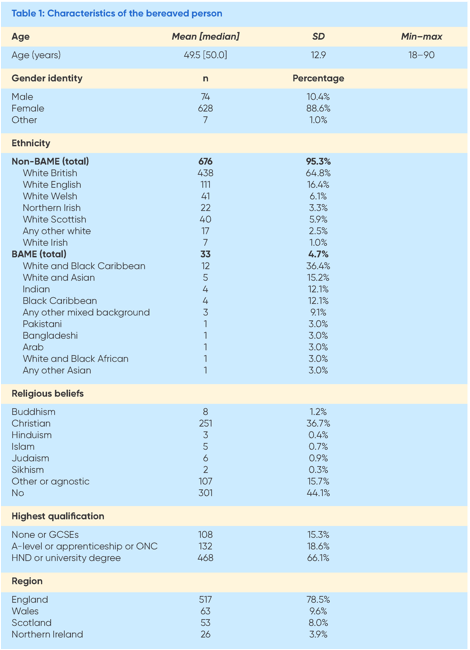

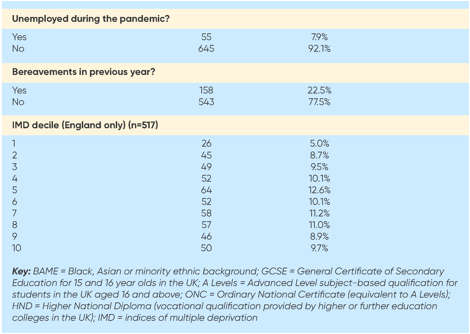

Sample characteristics

Participant

characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants represented diverse

geographical areas, deprivation indexes and levels of education. 88.6% of

participants were female (n=628); the mean age of the bereaved person was 49.5

years old (SD = 12.9; range 18-90). The most common relationship of the

deceased to the bereaved was parent (n=395,55.6%), followed by partner/spouse

(n=152,21.4%). 72 people (10.1%) had experienced more than one bereavement

since 16 March 2020. 33 people (4.7%) self-identified as from a minority ethnic

background. The mean age of the deceased person was 72.2 years old (SD=16.1;

range during pregnancy to 102 years) (Table 2). 43.8% (n=311) died of

confirmed/ suspected Covid-19, 21.9% (n=156) from cancer, and 16.7% (n=119)

from another life-limiting condition. Most died in hospital (n=410; 57.8%).

Experiences at the end of

life and in early bereavement

We found

almost all participants were affected by the restrictions placed on family

visiting in health and care settings, funerals and everyday social interaction.

These included restricted funerals (93%), limited contact with other close

relatives or friends (80%), loneliness and social isolation (67%) and being 'unable

to say goodbye as I would have liked' (64%). There was wide variation in

overall reported experiences of end-of-life care; for example, while 21.8%

reported they were always involved in decision about the care of their loved

one, 21.8% reported that they were never involved; 32.3% reported that they

were fully informed about the approaching death while 17.7% said they were not

at all informed (Selman et al, 2021a). Lack of support following the death was

a major issue, with 35.4% of participants reporting that they felt 'not at all'

supported by professionals immediately after the death. Similar problems have

been reported in pandemic bereavement studies conducted in the Netherlands, UK

and USA (Becque et al, 2021; Hanna et al, 2021; Mayland et al; 2021; Neimeyer

& Lee, 2021). Problems communicating with healthcare providers (HPCs)

related to difficulty getting information about their family member, being

misinformed about their condition and hospital policies and not being involved

in care or treatment decisions (Harrop et al, 2020;

Torrens-Burton et al, 2021). More positive experiences included being treated

with compassion and kindness, being able to visit, and relatives feeling that

they were kept well-informed about their family member's condition and care (Harrop et al, 2020). Again, these findings are consistent

with results from Dutch and UK studies (Becque et al,

2021; Hanna et al, 2021; Mayland et al, 2021).

We identified

several risk factors for problematic experiences towards the end of life and in

early bereavement including place of death and whether the death was expected

or not (Selman et al, 2021a). Deaths in hospital/care home compared with in

hospice/at home increased the likelihood of the bereaved person being unable to

visit prior to death or say goodbye as they wanted. By

contrast, deaths that occurred in hospice/at home, and deaths that were

expected increased the likelihood of the bereaved person being involved in care

decisions and feeling well supported by healthcare professionals after the

death. Bereavement due to Covid-19, compared with all other types of deaths,

decreased the likelihood of being involved in care decisions and of feeling

well supported by HCPs after the death, while increasing the likelihood of

being unable to say goodbye (Selman et al, 2021a).

Our

qualitative results demonstrate the emotional and psychological impacts of

these experiences (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021). People described the distress

and guilt caused by being unable to say goodbye and provide comfort to their

dying relative, as observed in the other UK study (Hanna et al, 2021; Mayland et al, 2021). Parents also described the added

confusion and upset caused to their children by being separated from

grandparents before the death (Harrop et al,

2021b). Having unanswered questions, regrets and doubts made it harder to

process and reconcile their feelings surrounding the death (Torrens-Burton et

al, 2021). Reflecting these difficulties, 60% of participants reported

experiencing high or fairly high needs for help 'dealing with my feelings about

the way my loved one died' (Harrop et al, 2021a).

Restricted funeral and memorialisation practices,

inability to support one another and mourn collectively also made it difficult

to find closure and begin to grieve (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021). These grief

difficulties are consistent with the quantitative findings of a US pandemic study, that 'disrupted meaning' contributed to worse grief

outcomes, and that higher levels of functional impairment occurred for

all deaths during Covid19 compared with pre-pandemic times (Menzies

et al, 2020; Breen et al, 2021).

Coping and informal

support during the pandemic

Participants

described the overwhelming and dehumanising effect of

being bereaved at a time of mass bereavement, with one in ten experiencing

multiple deaths. This was exacerbated by insensitive and

prolonged reporting of death statistics and other negative media coverage

(Torrens-Burton et al, 2021), observed also in analyses of UK media coverage

during the pandemic (Selman et al, 2021b; Sowden

et al, 2021). People found it harder to openly grieve, and experienced anger

and alienation in response to perceived government incompetence, conspiracy

theories questioning the pandemic, and public disregard of social-distancing

requirements and regulations (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021). Similar observations

were reported in an analysis of Twitter data from bereaved family members and

friends (Selman et al, 2021c) and another UK survey of bereaved people

conducted early in the pandemic (Sue Ryder, 2020). Adding to this upset, many

people described the further stress and distress that they encountered as they

tried to organise the affairs of their deceased

relative, particularly amidst the organisational

chaos of lockdown (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021). Around a quarter of

participants reported high/fairly high needs for help with administrative tasks

and accessing financial and legal information and advice (Harrop

et al, 2021a).

When

lockdown restrictions were in place, people struggled with not being able to

visit friends, engage in social and recreational activities and experience

respite from their situation. Fear of catching or spreading Covid-19 also

affected people's ability to cope and go about their daily lives, particularly

among those bereaved by the virus (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021). Consistent with

these challenges, around a half of people reported high/fairly high needs for

help with 'loneliness and isolation', 'feeling comforted and reassured', 'finding

balance between grieving and other areas of life' and 'regaining sense of

purpose and meaning in life' (Harrop et al, 2021a).

Social isolation and loneliness were also found to be especially prevalent

among people bereaved by a Covid-19 death and among bereaved partners (Selman

et al, 2021a). This contrasts with results from one of

the Netherland surveys, which found that satisfaction with social support did

not differ between people bereaved by Covid-19 versus other types of deaths (Eisma et al, 2021).

Most participants were supported by friends and family, but 39% reported difficulties

getting this support. A quarter reported that their friends or family were

unable to support them in the way that they wanted, with a fifth feeling

uncomfortable asking for help. People described how they missed being able to

hug their friends and family, and the difficulties they experienced talking

openly about their feelings, especially over the phone or internet.

A general lack of understanding and empathy within social networks was commonly

perceived. Due to the widespread stress caused by the pandemic, people worried

about adding to the emotional and mental health burden of friends and family,

who had their own issues to deal with. People also felt that (non-bereaved)

others could not understand what they were going through due to the exceptional

nature of pandemic bereavement (Harrop et al, 2021a).

Bereaved

people also commonly described problems relating to workplaces. These included

perceived insensitivity and a lack of understanding and compassion among

managers and colleagues. At a time of financial uncertainty, people were

disinclined to take leave from work out of fear of losing their jobs or livelihoods.

People in frontline jobs described difficulties managing their grief and

working in pressured, public-facing roles, while others described the isolating

effects of being furloughed or working remotely, which made it harder for them

to connect with and feel supported by their colleagues (Torrens-Burton et al,

2021).

For

families living together, lack of time and space during lockdowns, and periods

of school closure, made it harder for them to process and find respite from

their grief (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021). Although most parents felt that their

children were coping well with family-based support, some reported that their

children found it difficult to open up to them. Parents and guardians also

described the challenges of supporting their children while also struggling

with their own grief and trying to protect them (Harrop

et al, 2021b), a problem similarly observed among bereaved relatives in another

UK study (Rapa et al, 2021).

Participants

with children described the added strain caused to their children by school and

university closures, and associated disruption to their child's daily routines

and relationships. However, parents also positively described support received

through schools. Some children were receiving specialist emotional support,

which although helpful stopped during periods of school closure. Other parents

described the more general support provided by schools and teachers. Valued

features of this support included checking in on students during closure

periods, being aware of the student's bereavement circumstances and potential

problems, having informal conversations with students and their parents about

their grief, and proactively offering or placing students on the 'radar' for

specialist emotional support if needed (Harrop et al,

2021b).

Access to bereavement and mental

health services

We found

that just over half of our participants experienced high emotional support

needs and vulnerability in grief. However, three quarters of these more

vulnerable participants were not accessing bereavement counselling

or mental health support (Harrop et al, 2021a).

So what

explains this low uptake of formal support? Only 29% of people felt that they

did not need bereavement service support due to sufficient support from friends

and family (Harrop et al, 2021a), however 60% of

people had not tried to access bereavement services. Of those

who had sought support, over half experienced difficulties accessing these

services. People reported a lack of appropriate support, feeling

uncomfortable asking for support and being unsure if it would help them. Some

felt unhappy discussing their grief over the phone or video-call. There was

also a perceived need for Covid-19-specific bereavement support as well as for

culturally relevant and group-specific support for those with shared

experiences. People who lost elderly parents to long-term illnesses (and in

some cases Covid-19) felt less entitled due to the perceived greater needs of

others and the heavy demand being placed on services as a result of the

pandemic. People also reported not knowing how to access bereavement service

support (Harrop et al, 2021a). Relatedly, we found

that only a third of bereaved people had been given information about

bereavement support services, with those bereaved in non-hospice settings less

likely to be given this information, suggesting a missed opportunity for

provision of such information, especially in hospital and care-home settings

(Selman et al, 2021a).

Around a

quarter of parents described needing additional support from bereavement or

mental health services for their children, but in just over a third of cases

were not receiving this support. Reasons why some children and young people

were not getting the support they needed included unavailability of, or delayed

referrals to, mental health services due to the pandemic, long waiting times

for support, not knowing how to get support, preferences for face-to-face

support, and resistance from their children to receiving external support (Harrop et al, 2021b). Rapa et al (2021) report that only a

tenth of relatives bereaved during the pandemic were asked about their deceased

relative's relationships with children, further suggesting that important

opportunities for providing families with information about child grief and

support services may have been missed.

Conclusions

This synthesis

of results from the Bereaved during

COVID-19 study demonstrates the exceptional challenges of pandemic

bereavement, including high levels of disruption to end-of-life, death and

mourning practices as well as to people's social networks and usual coping

mechanisms. We identified considerable needs for emotional and therapeutic

support among bereaved people alongside significant difficulties in receiving

and accessing support, including for their children. Across our five

publications, we have made the following recommendations for improving the

experiences of adults, children and young people bereaved during and following

this and future pandemics.

1

Reducing

the trauma associated with death experiences, through improved communication

with and involvement of families (Selman et al, 2021a), safe facilitation of

family visiting to healthcare settings, and, where this is not possible,

connecting families and loved ones through accessible remote communication

methods (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021).

2

Improving

family support immediately after a death, including routinely providing

opportunities to discuss patient care and the circumstances of the death, and

information about locally and nationally available bereavement support for

adults, children and young people (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021).

3

Greater

resourcing and expansion of national and regional adult and child bereavement

services, including culturally-competent support, tailored to the needs of

those bereaved during the Covid-19 pandemic, and specific support for groups

with shared experiences and characteristics.

4

Implementing

strategies to improve awareness of bereavement support options for adults and

children and young people, including information on services, self-help

resources and materials for different age groups, promoted and made available

online and in community settings (Harrop et al,

2021a, 2021b).

5

Mitigating

loneliness and social isolation, including flexible support bubble arrangements

for the recently bereaved when restrictions are in place and informal

community-based interventions aimed at strengthening social networks, grief

literacy and communication skills, with regards to children and adults (Harrop et al, 2021a, 2021b).

6

Training

for school staff to have age-appropriate conversations with students around

grief and bereavement, and to be able to identify when a child might need

additional specialist support. During lockdown periods of school closure

specialist programmes should continue for existing

students (remotely if needed), while also proactively identifying and engaging

with newly bereaved families who may need support (Harrop

et al, 2021b).

7

Developing,

promoting and adhering to guidance and best practice recommendations regarding:

a) funeral options during times of social restrictions, b) supporting those

administering the death of their deceased relative, and c) supporting bereaved

employees (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021).

8

Providing

opportunities for remembrance, greater respect and listening to those bereaved.

This means recognising the potentially dehumanising and alienating consequences of death

statistics and conspiracy theories in mainstream and social media; facilitating

national and local initiatives which support private and public remembrance;

and inclusive consultation with those recently bereaved (eg

via the UK Commission on Bereavement: bereavementcommission.org.uk) to improve

support for bereaved people and ensure lessons are learned for future

pandemics. (Torrens-Burton et al, 2021).

References

Becque

YN, van der Geugten W, van der Heide

A, Korfage IJ, Pasman HRW, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD et al (2021) Dignity

reflections based on experiences of end‐of‐life care during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic: A qualitative inquiry among bereaved relatives in the Netherlands

(the CO‐LIVE study). Scandinavian

Journal of Caring Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.13038

Breen LJ,

Mancini VO, Lee SA, Pappalardo EA, Neimeyer RA (2021) Risk factors for dysfunctional grief and

functional impairment for all causes of death during the COVID-19 pandemic: The

mediating role of meaning. Death Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1974666

Eisma MC,

Tamminga A, Smid GE & Boelen PA (2021) Acute grief after deaths due to COVID-19,

natural causes and unnatural causes: An empirical comparison. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 278, 54–56.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.049

Harrop E,

Farnell D, Longo M, Goss S, Sutton E, Seddon K et al (2020) Supporting people bereaved during

COVID-19: Study Report 1, 27 November 2020. Cardiff

University and the University of Bristol. Available at:

www.covidbereavement.com (accessed 4 December 2021).

Harrop

EJ, Goss S, Farnell DJ, Longo M, Byrne A, Barawi K et al (2021a) Support needs and barriers to

accessing support: Baseline results of a mixed-methods national survey of

people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliative Medicine.

https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211043372

Harrop E,

Goss S, Longo M, Seddon K, Torrens-Burton A, Sutton E

et al (2021)b Parental perspectives on the grief and

support needs of children and young people bereaved during the Covid-19

pandemic: qualitative findings from a national survey. medRxiv 2021.12.06.21267238.

https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.06.21267238

Hanna JR,

Rapa E, Dalton LJ, Hughes R, McGlinchey T, Bennett KM

et al (2021) A qualitative study of bereaved relatives'

end of life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliative

Medicine, 35(5) 843–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211004210

Mayland

CR, Hughes R, Lane S, McGlinchey T, Donnellan W, Bennett K et al (2021) Are public health

measures and individualised care compatible in the

face of a pandemic? A national observational study of

bereaved relatives' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliative

Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211019885

Menzies RE, Neimeyer

RA, Menzies RG (2020) Death anxiety, loss, and grief

in the time of COVID-19. Behaviour Change, 37(3)111–5.

https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2020.10

Neimeyer

RA, Lee SA (2021) Circumstances of the death and associated risk factors for

severity and impairment of COVID-19 grief. Death Studies, May 21, 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1896459

Rapa E,

Hanna JR, Mayland CR, Mason S, Moltrecht

B & Dalton LJ (2021) Experiences of preparing children for a death of an

important adult during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods study. BMJ open.

Aug 1, 11(8):e053099.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053099.

Selman LE, Farnell DJ, Longo M, Goss S, Seddon

K, Torrens-Burton A et al (2021a) Place, cause and expectedness of death and

relationship to the deceased are associated with poorer experiences of

end-of-life care and challenges in early bereavement: Risk factors from an

online survey of people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv.

https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.09.21263341

Selman E, Sowden R & Borgstrom E

(2021b) 'Saying goodbye' during the COVID-19 pandemic: A document analysis of

online newspapers with implications for end of life care. Palliative Medicine.

https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211017023.

Selman LE,

Chamberlain C, Sowden R, Chao D, Selman D, Taubert M et al (2021c). Sadness, despair and anger when a

patient dies alone from COVID-19: A thematic content analysis of Twitter data

from bereaved family members and friends. Palliative

Medicine, 35(7) 12671276. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211017026

Sue Ryder

(2020) Bereaved people claim lockdown deaths became just a statistic. Available

at: www.sueryder.org/news/bereaved-people-claim-lockdown-deaths-became-just-a-statistic

(accessed 4 December 2021).

Sowden R,

Borgstrom E, Selman LE

(2021) 'It's like being in a war with an invisible enemy': A document analysis

of bereavement due to COVID-19 in UK newspapers. PLoS

one. 16(3):e0247904.

Torrens-Burton

A, Goss S, Sutton E, Barawi K, Longo M, Seddon K (2021) 'It was brutal. It still is': A qualitative

analysis of the challenges of bereavement during the COVID-19 pandemic reported

in two national surveys. medRxiv

2021.12.06.21267354. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.06.21267354

Acknowledgements

Our thanks

to everyone who completed the survey for sharing their experiences, and to all

the individuals and organisations that helped

disseminate the survey. We would also like to thank our research team and

advisory group members for their contributions to the study.

Funding

The Bereavement during COVID-19 study is funded by the UKRI/ESRC (Grant No. ES/V012053/1). Emily Harrop's post is supported by Marie Curie core grant funding to the Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Centre, Cardiff University (grant MCCC-FCO-11-C).