How

was your lockdown?

Reflections

of a therapist during the Covid-19 pandemic

Julia Samuel

Vice President, BACP; Founder Patron, Child Bereavement UK

Key words

lockdown, therapy, grief, debrief

I am

regularly asked 'how was your lockdown?'

It is a

good question. My brief answer is that I was busy. I did not make sourdough or

learn to play an instrument; I worked. Harder than I have

ever worked before.

In this

article I would like to explore what that meant at a deeper level, both

psychologically and practically; as a therapist, a

woman and my multiple other roles. What were my challenges and what helped me

keep my head above water? What have I learnt? I write this in the frame that 'the

personal is the most universal,' the wise words of Carl Rogers, in the hope

that you will identify aspects of yourself in my experience that may resonate

with you, or not. Whatever your response is, it might give you insight for your

own reflections – on your

role in this broad field of bereavement care and research.

*

In my

training, when asked that familiar question, 'why did I want to be a therapist?'

I moved quickly from that common, and not inaccurate, understanding 'I want to

help people, I like being needed' to recognising that

I gave what I most wanted to receive. Additionally, I became aware that being

in meaningful relationship was profoundly important to me. My curiosity was

fired by what was going on below the surface, rather than what people showed. I

came to see that being a therapist was by no means an altruistic endeavour but one that met my needs as well as having the

satisfying aim of supporting my clients. The roots of this

was certainly in my childhood and of course, being human; we are wired

to relate and connect. For over 30 years in my supervision and therapy I

regularly negotiate how those forces influence my practice. The reason I tell

you this is that the pandemic turned the volume up on all those responses. In

the crisis I had a greater drive to want to help, to meet the needs of others

and form close relationships.

This

initially showed itself by me offering to support a UK National Health Service

(NHS) team of medical staff working in an intensive care unit. Two consultants

liaised with me, and we decided on two lunchtime slots, of an hour, every week.

I would be one side of the Zoom call and the team would be in the staffroom

talking to me through a phone; taking it in turns to express the full gambit of

emotion that you can imagine someone would feel in that situation. For confidentiality

reasons I can only tell you my experience.

I gained a

lot from being useful. Being part of the NHS, even in this tiny way, gave me a

sense of belonging and purpose as we faced this crisis, which anchored me.

Fortunately, I was able to draw on decades of experience supporting medical

staff in the NHS, which has left large reserves of respect and warmth for all

health professionals. Those foundational responses stayed with me throughout

the tumult of the work and centred me – and I

think were felt by the team. We quickly developed the underlying key to a

therapeutic relationship – trust – and formed a working alliance.

It was

intense. My journal reminds me of some of my process: 'I always feel bad that

somehow I can't offer enough, but I was glad they talked ... so touched by the

care they give patients.' Another one: 'I was proud today, excellent session ...

they were emotionally honest, and it felt an important part of keeping the team

together ... we discussed some useful coping strategies.' Or, 'a painful

session, I was tense, worried that we all felt worse afterwards!' There were

nights I woke with anxiety from difficult images and stories. Wonderful moments

of black humour, raucous laughter, which sparked

warmth and connection and a defence yes, but also a

healthy protection in the face of the difficulties.

The

pandemic had thrown us all into an alien and frightening landscape of grief.

Grief is a messy, chaotic, unpredictable, subjective business. It often

switches our autonomic nervous system to code red. Part of my professional

practice is to find ways to keep myself centred when

those I'm working with are suffering. I use habits like exercise to balance me:

also theories as frameworks to turn to help me understand what is going on in

the therapy. My pivotal theory is the dual process model (Stroebe

& Schut, 1999). I like the dynamic oscillation

between restoration orientation and loss orientation, the movement between the

two. Allowing people to confront their pain and in restoration to avoid it.

Often people describe grief as hitting them in waves. This theory allows for

that, and allows for our natural survival mechanism, giving ourselves

opportunities to have a break from the pain, to be distracted, have a plan, and

most importantly have hope. It is hope that turns a life around. It discusses

gender norms; men tend to be restoration oriented, and women tend to be loss

oriented. I describe this theory to clients and told the ICU team about it;

they too found it helpful to have a theory that helped them understand and

accept themselves.

As I

reflected then, and with more clarity now, the team was my client. There was a

parallel process.

I felt as

powerless as them in the face of multiple difficult and traumatic deaths. (Of

course, they saved many lives as well.) We were all in the helping profession,

we wanted to make a difference and in our own way had to recognise

the limits of what we could offer; accept that simply being present is of value

– important. The curative power of listening,

witnessing, being alongside someone, offering heartfelt care. Although

working with many people was more of a psychological juggle, and it was

therapeutic rather than therapy,

I drew on

similar knowledge, skills and practice that I would with a one-to-one client.

The

emotional turmoil they lived was transferred through the screen to me, bodily.

I felt surges of fear which I acknowledged: 'gosh that's

frightening to even hear, it must have been...' and breathed into it, allow,

but not act on. It was my job to hold steady, to listen, be an empathic

presence who named the team's process; explore their individual difficulties,

listen as they expressed their feelings, gain insight and through the

collective sharing a normalisation of what they felt

– they weren't failing by being distressed. Helping them recognise not to conflate their feeling with fact; they may

feel they've failed if someone dies, but that does not make it so. Those

responses are common in my one-to-one therapy too. Often the first step with a

client is letting them know that however 'mad' or 'bad' they might feel, what

they are feeling is normal in grief. Rather than self-attack, which can be a

cruel default response in grief, encourage them to hold the messages from both

their head and heart side by side. Hold the discomfort of feeling guilty while

knowing they aren't actually guilty.

The team

had to go straight from the session into the intensive care unit, so it was

important to find a balance. As with all therapy it was a dance, of moving in and out – allowing and letting go. Using

myself as a reference point as to what was going on. Trusting my instincts on

how to respond, some worked, some didn't – I'd check what I missed and

reconnect. Sometimes offering practical ideas;

demonstrating breathing exercises, suggesting walks in nature. Using my voice

and presence to contain strong feelings. It was turbulent, with missteps from

me, but overall we did what we contracted to do: emotionally support the

individuals in the team, which built resilience in the whole team, to manage

themselves as they worked in the ICU.

Comparing

this to my individual clients; I would explore at

greater depth their internal process, perhaps use Gendlin's

(1982) felt sense to help them access their bodily wisdom. Working to align

their mind–body connection, to find both the narrative they are telling

themselves and what the emotional signals their body is transmitting to them

mean. Creating a safe place where they come to trust that, as difficult as it

is, pain is the agent of change. That paradoxically by allowing themselves to feel the pain of loss, voice it, express it,

is what over time allows them to heal. It is what they do to block and anesthetise their pain; alcohol, food, sex, or busyness to

name but a few, that over time leads to long-term negative consequences.

*

The demand

in my private practice was immense. My experience was that my clients'

pre-existing difficulties were intensified. If they had anxiety their fear

ramped up. If they were grieving, having their usual social support and

structures removed overnight meant many fell into despair. Some clients were

dying which meant the very precious time they had left was not spent with their

children or grandchildren, their last chance to be present at significant

events was cancelled. Everything medical was supremely challenging.

Those new clients who were bereaved through Covid

suffered traumatic grief; not being at the bedside, or the graveside, having no

rituals or connected support. Their sense of frozen surreal grief, agonising

as it was, is only now beginning to thaw. It will be a long road.

To sum it

up, I saw more suffering in the last 18 months than I have seen in my three

decades as a therapist. It was devastating. And their suffering was invisible,

locked away in people's minds and homes. The mental health

pandemic running beneath the health pandemic. I believe the greatest

psychological pain was inflicted by the isolation. When people we love die, we

need the love of others to help us survive. Their presence,

their hugs and, yes, their dishes of lasagne.

The path to recovery in grief needs to be paved with people and in the time of Covid it was a chilly emptiness. The fallout has not been

reckoned with and I have no doubt it will inform the content of our therapy

rooms for years ahead.

*

To finish on a personal note. I was unquestionably seduced by being needed; when I felt most overwhelmed by my own fear being busy and

useful was my defence to cope with it. I see again

(not exactly rocket science) that under duress I, and most of us, revert to

default modes of coping, and in the future really clocking that early might

enable me to make better informed choices.

I paid a

price for being that busy. I didn't see my family as much as I would have

liked. I wondered, did my clients get the best of me,

with my family getting the dregs? I felt guilty and it echoed earlier guilt as

a parent.

On the

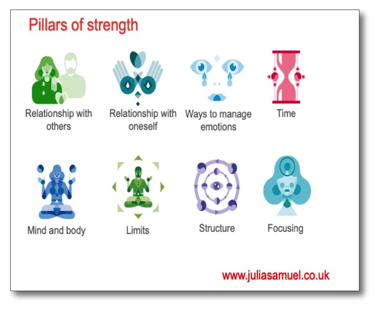

positive side I have good habits that enable me to stay sane and healthy. They

are based on my 8 Pillars of Strength (see below) where I take lots of exercise,

meditate, and am self-compassionate. My time boundaries held. I always stopped

work at a reasonable hour. I ate with my family, watched a great deal of only

happy television (much to my husband's irritation), and laughed and hugged

– a lot. That physical holding was emotionally vital for me.

What have I learnt? To state the obvious, crises are a complex, extreme

business. I found it demanding and rewarding in equal measure. I need to pay

attention to how seduced I can be by my work. It has magnified my respect for

the power of the human spirit. I am in awe of my clients, for both expressing

their pain and their strength.

How we

spend our days is how we spend our lives, time is precious. Use it mindfully.

I believe

more profoundly that love is what matters most.

Fundamentally

I am grateful for being in a profession that I truly love. To quote Freud, 'Love

and work, work and love is all there is.'

References

Gendling E (1982) Focusing. Bantam Books.

Stroebe MS & Schut HAW (1999) The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death studies, 23(3) 197–224.

Further reading/resources

Action for Happiness www.actionforhappiness.org

Beattie G (2004) Visible thoughts: the new psychology of body language. Routledge.

Ben-Shahar T (2011) Happier: Learn the secrets to daily joy and lasting fulfillment. McGraw Hill.

British Psychological Society (2008) 2008 psychological debriefing www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/evidence/resource/other_complaints_q5.pdf?ua=1

Damasio A (1999) The feeling of what happens: Body, emotion and the making of consciousness. Heinemann.

Department of Health (2005) When a patient dies. https://bereavementupdate.blogspot.com/2005/12/department-of-health-uk-when-patient.html

Duhigg C (2012) The power of habit. Random House.

Gibbs (1998) Reflection model. www.ed.ac.uk/reflection/reflectors-toolkit/reflecting-on-experience/gibbs-reflective-cycle

Kabat-Zinn J 2012 Mindfulness for Beginners: Reclaiming the Present Moment-and Your Life. Sounds True.

Kabat-Zinn J (2001) Full catastrophe living: How to cope with stress, pain and illness using mindfulness meditation. Doubleday.

Mehrabian A (1972) Nonverbal communication. Aldine-Atherton.

Mind (2017) Food and mood. www.mind.org.uk/information-support/tips-for-everyday-living/food-and-mood/about-food-and-mood

Pennebaker JW (2004) Writing to heal: A guided journal for recovering from trauma and emotional upheaval. New Harbinger Press.

Pennebaker JW (1997) Opening up: The healing power of expressing emotion. Guilford Press.

Samuel J (2017) Grief works: Stories of life, death and surviving. Penguin.

Schut HAW, Stroebe MS, Boelen PA & Zijerveld AM (2006) Continuing relationships with the deceased: Disentangling bonds and grief. Death Studies, 30, 757–766.

Schore A (2003) Regulation and the repair of the self. Norton Books.

Tedeschi RG & Calhoun LG (2012) Resilience: the science of mastering life's greatest challenges. Cambridge University Press.